MASSIVE GLIDING TREEFROG BREEDING AGGREGATIONS AT SHAMPOO PONd

It was about 06:00 after a night-long of heavy rain ended a short dry spell, and already you could hear a deafening chorus of creatures gathering at the pond. Though sleepless and mosquito-ridden, we trudged chest-deep through the murky swamp waters with notebook and camera in hand to reach the source of the chaos. That’s when we saw it: One of the largest aggregations of treefrogs likely ever to be seen.

Tens of thousands of adult gliding treefrogs (Agalychnis spurrelli) literally poured over each other in attempt to breed and lay eggs. And for two Costa Rican tropical biologists and herpetologists, this rare biblical magnitude of frogs was like heaven on earth. This is Costa Rica. This is Osa. This is “Shampoo Pond”.

Since 2015, I have been studying how frog embryos use environmental cues to change their behavior. My current Ph.D. research in Osa aims to understand how specific reproductive strategies interact with both environmental cues and development to affect embryo behavior and survival.

For these gliding treefrogs, tens of thousands of reproducing adult frogs mean hundreds of thousands of frog eggs and embryos. And in this species, embryos are left alone to fend for themselves after they are laid. That means this event leaves behind a massive all-you-can-eat frog-egg buffet for hungry predators

Why does a massive population lay their helpless eggs all at once in one location? That’s a great question, and it’s one I hope to answer!

In some cases, an overwhelming amount of prey can function as an antipredator adaptation if, for example, the overabundance of frog eggs decreases the probability of any one egg’s chance of being eaten. Basically, it can serve as a form of “safety in numbers”. This is known as predator swamping (or predator satiation). Shampoo Pond offers a pristine ecosystem where this hypothesis can be tested using these treefrogs. In 2018, with the assistance of Katherine González, a Costa Rican tropical biologist, I conducted initial egg clutch monitoring studies in the hopes of determining whether this reproductive strategy has any impact on offspring survival. But this system has even more to it!

If undisturbed, gliding treefrog embryos develop and hatch into the pond as tadpoles in 6 days. But with so many threats, many wouldn’t survive that long. How can frog heaven get any more interesting, you say? Well, what makes these treefrogs particularly interesting is their ability to respond to threats by hatching prematurely!

That’s right! These embryos can hatch almost 40% early to escape the jaws of hungry predators like snakes, wasps, and even monkeys! However, many of them don’t hatch early, and thus will die during predator attacks. We know the embryos have the ability to hatch early, but sometimes they don’t. Why?!

In addition to predation, these embryos are susceptible to desiccation, fungal infection, and flooding. These threats provide unique cues, which the embryos use to inform their decision of when best to hatch. This is called environmentally cued hatching, and it’s presumably a very adaptive embryo behavior—it increases their survival and fitness. But for the gliding treefrog, this behavior may not be as plastic or adaptive as in other species. Here in the Osa, another focus of my research is understanding the mechanisms which cause these embryos to hatch or not to hatch in these contexts at different developmental stages.

Our work has only begun at Shampoo Pond, and we hope that it will elucidate the conservation importance of this fragile ecosystem and its inhabitants, particularly amidst the current anthropogenic environmental changes in Neotropical rainforests.

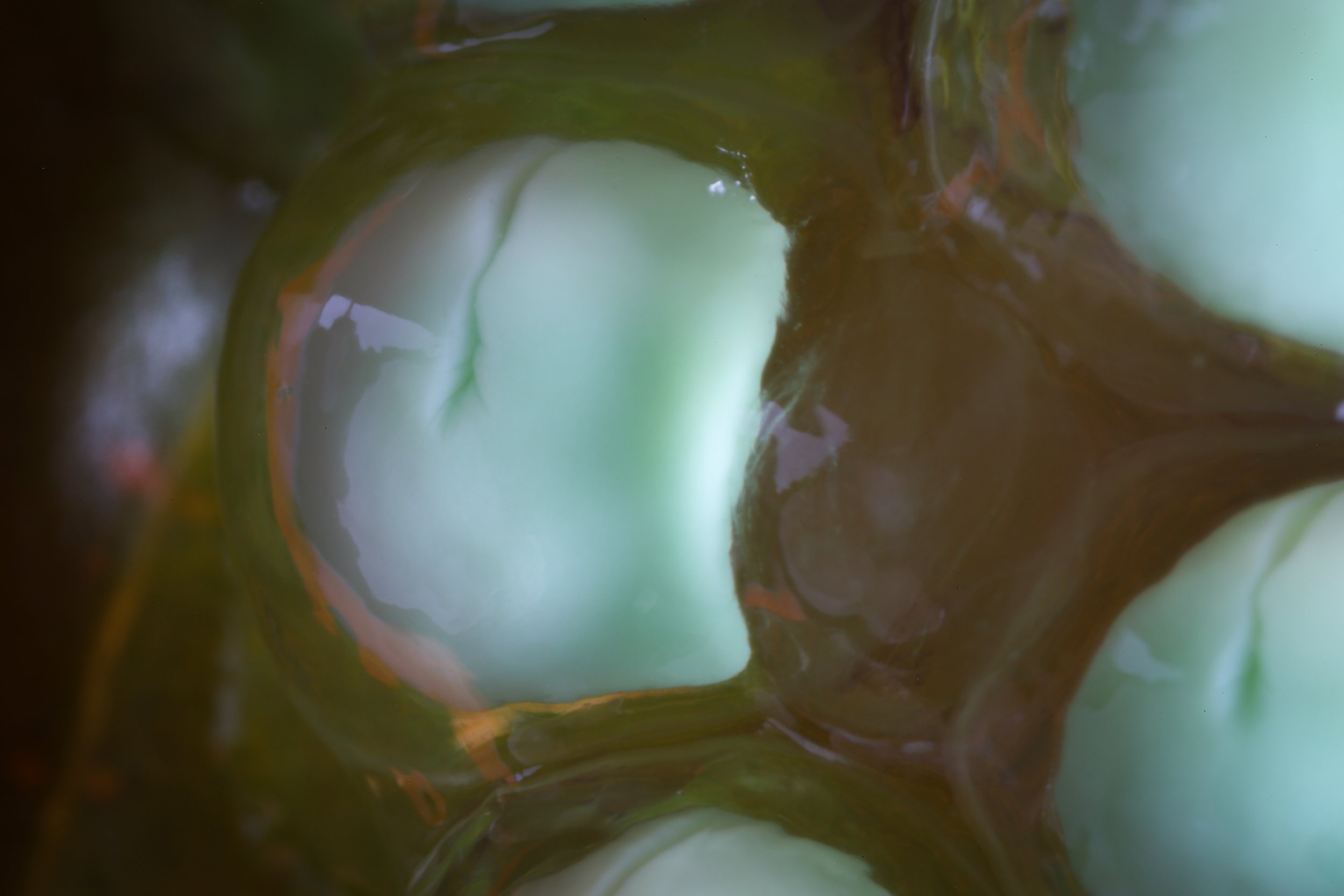

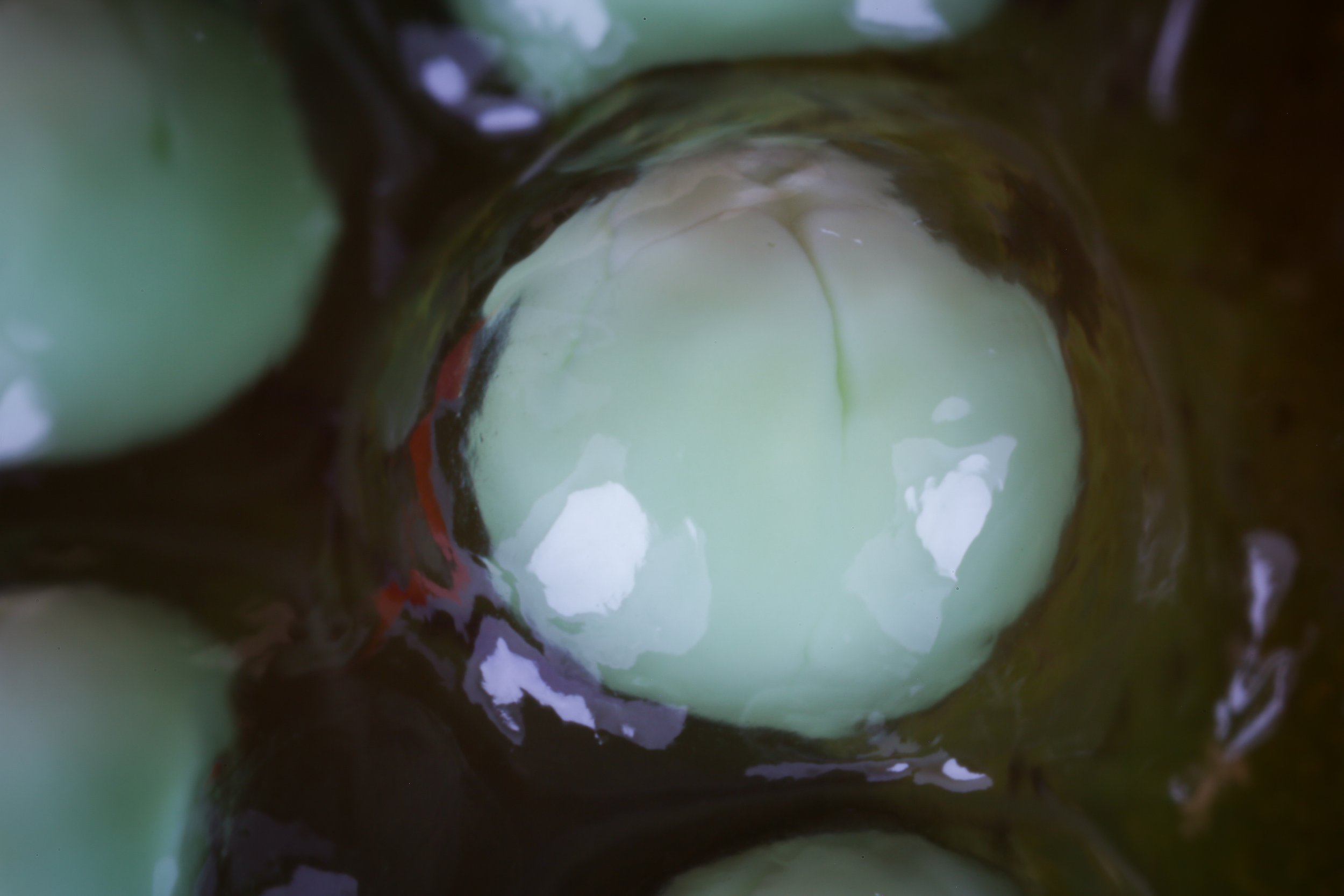

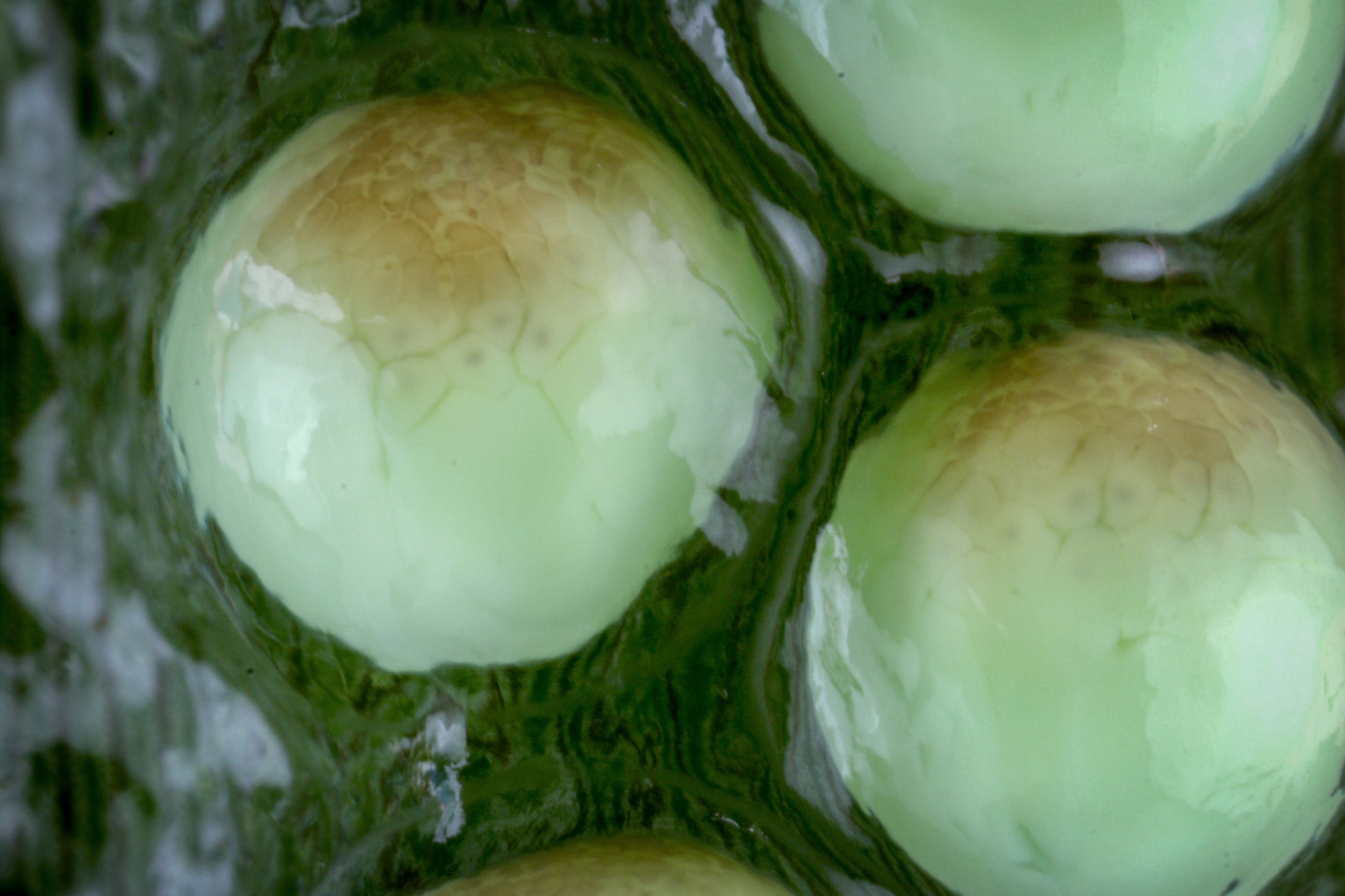

Above: A developmental series of gliding treefrog (Agalychnis spurrelli) embryos . After embryos undergo early and late cleavages (cell divisions with visible nuclei), they form the dorsal lip and the yolk plug becomes visible. Later, embryo bodies rise and begin to show muscular response as the external gills form. Then, their hearts begin to pump blood throughout the body and external gills, and they begin to develop pigmentation. At three and four days, embryos begin to respond to environmental cues and can hatch prematurely to escape flooding and predators respectively. In the last picture, I collect eggs at Shampoo Pond to study.